by Jane St. Clair

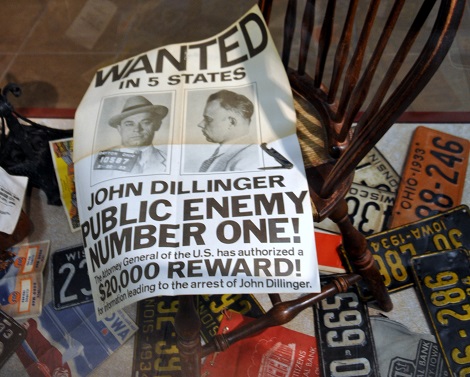

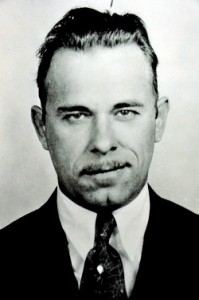

In the middle of the Depression a bank robber named John Dillinger became the FBI’s first Public Enemy Number 1. Every police officer and G-man in the country were out to get him.

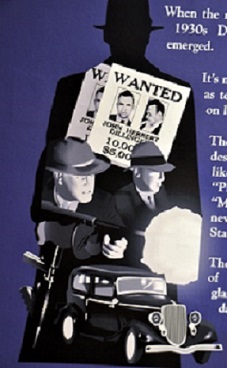

Even though he was Public Enemy #1, the public liked John Dillinger. The public did not like banks because they took away houses and farms, but they did like the cool, handsome Robin Hood who robbed banks. Dillinger would spray the air with machine gun fire and then ride off in his getaway car. Everyone liked Dillinger so much that the Hudson Motor Company advertised one of their models as the car John Dillinger used.

Dillinger would spray the air with machine gun fire and then ride off in his getaway car. Everyone liked Dillinger so much that the Hudson Motor Company advertised one of their models as the car John Dillinger used.

Today Dillinger and his gang are not as famous as Bonnie and Clyde, mostly because Bonnie and Clyde had a better movie. But back in the day, Dillinger was the bigger deal. In fact,  he stole 16 times more money in one year than Jesse James did in his entire career.

he stole 16 times more money in one year than Jesse James did in his entire career.

In the winter of 1934, Dillinger and his boys –Harry Pierpont, Charles Makley and Russell Clark– needed a vacation.

Like typical winter visitors to our fair city, they were looking to relax in a warm place. They believed police in a hick town of 30,000 would be too dumb to get them. Tucson’s police department had 34 guys who earned $140 a month — small potatoes to the Dillinger Gang who had evaded cops in four states and Hoover’s G-men and stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars.

On January 25, Charles Makley and Harry Pierpoint checked into a third floor room at the Congress Hotel.

Fire broke out that night in the hotel basement. The clerk at the switchboard phoned every guest in the hotel, including Dillinger’s friends, and told them to leave at once.

Later the fireman who pulled them to safety remembered how heavy their suitcases were. Makley had tipped them $12 to retrieve the luggage and pull it down the aerial ladder. His suitcase was heavy because it contained pistols, bullet proof vests, machine guns, rifles, and $23,000 in cash.

The next day the firemen were sitting around the firehouse, smoking, eating chili and reading True Detective magazine, which is what they did when nothing was on fire.

As they thumbed through the pictures, one guy recognized the two men from the night before, and he tipped off the police.

Officers nabbed Makley at Grabbe Store downtown where he was buying a radio capable of picking up police calls. Pierpont and Clark were taken at a gas station and the Close-In Motel on 6th Avenue. Dillinger was arrested at 927 E. Second Avenue near the University of Arizona. He was so surprised that all he said was, “I’ll be damned.”

It was the arrest of the century, and it had been pulled off without anyone firing a shot. The gang was sent back to the Midwest to face charges of murder, robbery, and other offenses.

Dillinger escaped from prison in Indiana by using a fake gun he made from wood and painted with shoe black polish. On July 22, police and G-men killed him with four gunshots in front of the Biograph Theater in Chicago.

The famous “Woman in Red” had given him up in exchange for a promise of not being deported to Romania.

Makley was killed by police during a prison escape. Pierpont got the electric chair.

Russell Clark was in prison for 34 years and died four months after his release.

The Tucson police officer who arrested Dillinger got to keep Dillinger’s bullet-proof vest, and today his badge hangs in the Arizona History Museum on Stone Avenue.

The Hotel Congress is now a historical site.

The Woman in Red got the reward money and then the U.S. government deported her to Romania.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

You can see Dillinger stuff at the Arizona History Museum at 140 North Stone, Tucson, and more Dillinger pictures on “The Arizona Historical Society Website”